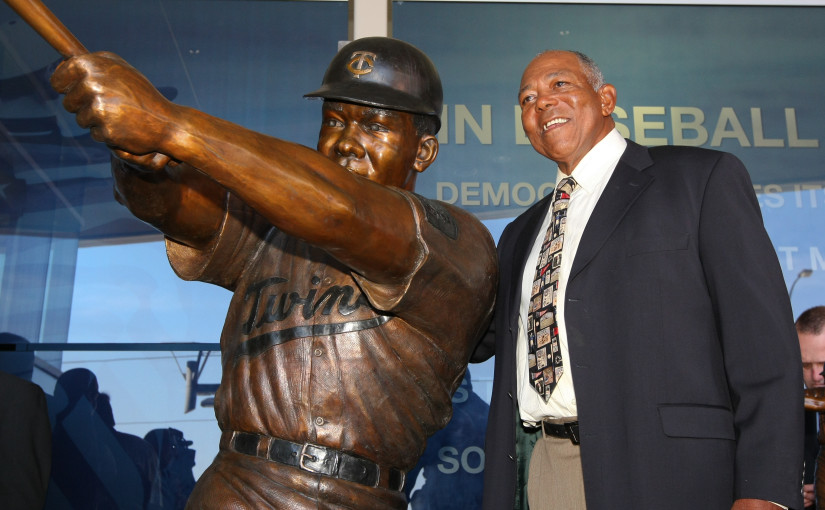

Image caption: To honor his great career and his retired No. 6 jersey, the Minnesota Twins dedicated this statue to Tony Oliva in 2011 at Gate 6 at Target Field.

By Ron Thomas

(The following is the introduction I read before presenting Oliva with a Pioneer Award from the National Association of Black Journalists Sports Task Force on August 7.)

If not for Fidel Castro, Tony Oliva probably would not be one of our honorees today.

One of the great hitters of the last half-century, Oliva was raised in rural Cuba, where baseball is revered. He played only on Sundays, and he learned how to hit as his brother pitched to him.

“I told him any time you strike me out you get a nickel, and he had to work hard to strike me out,” Tony said.

In 1959, Castro overthrew the dictatorial Cuban government. The next year, the Washington Senators signed Tony to a contract before moving to the Twin Cities, and in January of 1961, the U.S. broke off diplomatic relations with Cuba. Using his brother’s documents to leave, Tony (whose real first name is Pedro Jr.) was allowed to fly first to Mexico and then to the States for a tryout with 21 other Cuban players. They were the last baseball players to leave Cuba without defecting.

The lucky break that made a career

At spring training in Fernandina Beach, Florida, Tony was cut presumably because of poor fielding, but he believes racism was the real reason. Only two minor-league teams were left in spring training when the Cubans had arrived. The Erie, Pa., team had already chosen one black player, and the other team from Florida didn’t want any, so Tony was supposed to be sent home. But because of the Castro-U.S. feud, there were no boat or plane rides to Cuba.

A minor-league manager named Phil Howser got a rave report on Tony so he paid Tony’s expenses until Howser found a team that would take him in Wytheville, Virginia. There he hit .410, and a stellar career was born.

Unlike many of today’s hitters who will get a three-ball count and then settle for a walk, Tony stayed aggressive at the plate. Regardless of the count, if a pitcher threw what he calls “a Cuban sandwich,” Tony tried to crush it.

Instant star

He made history by leading the American League in batting in his first two full major-league seasons, hitting .323 in 1964 and .321 in 1965. Despite a serious mid-career injury that resulted in eight surgeries and a replacement of his right knee, from 1962-76 Tony batted .304 with 220 home runs, 947 RBIs, 8 straight All-Star Game appearances and five finishes among the top 10 vote-getters for the MVP award.

Last year, Tony was deeply disappointed when he missed being selected for the Hall of Fame by one vote. But this year brought him joy when President Obama re-opened U.S. diplomatic relations with Cuba.

“Hopefully, more people will enjoy a chance to enjoy Cuba and see for themselves what kind of people Cuban people are – very nice, very friendly,” Tony said. “I have five brothers and sisters and I go back every year.

“Now I have two countries. I live 55 years in the United States and 21 in Cuba. I am very proud of both countries.”

Tony, please come to the podium for being one of the most lethal hitters of our time.

Image caption: Tony Oliva with (L-R) me, Morehouse graduate Jeffrey Washington ’10, past Maroon Tiger Editor-in-Chief Jayson Overby and Thomas Scott ’13