Dunking, a foundation of today’s NBA, used to be a guilty pleasure done in the privacy of casual workouts or a team’s practice in the 1940s and ’50s. Just driving down the lane during a game was frowned upon. “We had a saying, ‘Nobody comes through the middle without a ticket,’ ” recalled Earl Lloyd, the first black player to participate in an NBA game.

So, throwing down a slam would have been considered a rude attempt to embarrass an opponent, probably one worthy of a fight in the NBA’s Wild West days when brawling was acceptable.

But extraordinary leapers like Joe Caldwell and Connie Hawkins made dunking a crowd pleaser in the 1960s and ’70s, and the era of “The Last Dance” produced airborne creative geniuses who were admired and feared during the 1980s and ’90s. That’s why I wrote this third installment of my Sunday basketball profiles. Here are the roots of today’s article:

I interviewed some of the greatest dunkers of all time mostly at the 1986 NBA All-Star Game for a story about the sport’s amazing skywalkers. But that game will forever be remembered for producing the most unexpected Slam Dunk champion of all time, 5-foot-7 Spud Webb. I hope you enjoy “NBA Elite – Games Above the Rim” (SF Chronicle, March 19, 1986) and “Spud Webb Takes Off to New Heights” (SF Chronicle, Feb. 10, 1986).

By Ron Thomas

They are the daredevils of the NBA – the skywalkers who soar, swoop, dip and slither in midair to score points and thrill crowds.

“Going above the rim and making a play,” says Julius Erving, the unofficial captain of the skywalkers’ air corps, “blocking a shot, pinning a ball on the glass, dunking the ball, bringing the ball down then, taking it back up – that’s the stuff dreams are made of.”

Not to mention reputations.

Erving, Dominique Wilkins, Michael Jordan and James Worthy explore the atmosphere around and above the rim in a way few mortals can.

All are small forwards or big guards – the positions that seem to have the best combination of size, strength and flexibility – and they symbolize the playing-in-the-air artistry more prevalent now than ever in the NBA’s 40-year history.

But by “daring to be great” – one of Erving’s personal mottos – they also expose themselves to serious injury.

“The element of danger doesn’t really enter the priorities you think about when you’re on the ground,” Erving said. “It’s right up there one or two when you’re above the rim.

“Where am I going to land, and who’s going to be under me? Is it going to be some guy who will take my legs and put them where my head was, or will this be a safe flight and a safe landing?”

When Erving goes up, he says he’s always looking or feeling for “ground space.” Sometimes, opponents provide it. “If guys see you coming down wrong, they’ll catch you to keep you from hurting yourself,” Wilkins said.

Other skywalkers don’t acknowledge the danger. “I’m so used to it now, there’s no fear,” Jordon said.

Skywalking was a stranger to the NBA until the late 1960s, when Elgin Baylor and Johnny Green joined the league. They both are black, and in the 1990s, eagle-like thrusts to the basket became more common as the number of black players increased.

Tom Sanders, a Boston defensive star in the ’60s, said black players learned to defy gravity because they concentrated on developing their skills more than white players.

In addition, basketball is king in predominantly black urban areas, where there is a scarcity of playing space and money required for other sports (such as golf and tennis).

“It comes down to the number or blacks who take the game seriously,” Sanders said, adding a personal concern that too many young players place basketball above academics.

Sanders said that when he played, every team had at least one player with extraordinary leaping ability – Connie Hawkins, Joe Caldwell – but there was much less dunking because of a popular defensive philosophy.

‘If you make me look bad, I may hurt you a little bit.’ – ex-Celtic Tom Sanders

Today, dunking and playing in the air are accepted fundamentals of pro basketball, says Lakers coach Pat Riley, executed best by “disciplined leapers” who have tremendous body control.

“It’s the evolution of the athletes,” Riley said. “The training methods and their physical makeup have changed the game. It’s being played much higher and taller than in the past.”

In skywalking, there is no prepared flight plan. Says WiIkins: “I just do whatever comes to mind.”

So does Worthy, who credits skywalking to “God-given talent” and spontaneity.

“You run into obstacles you don’t expect when you first take off,” he said. “Once you run into them, creativity is just automatic.”

A few years ago, Worthy pulled off one of the most sensational moves ever seen in the Coliseum Arena when he went up for a baseline shot, spun 360 degrees around the Warriors’ Larry Smith, then banked in a jumper.

Credit it to planned spontaneity.

Earlier in the game, Smith had blocked two of Worthy’s shots after Worthy had eluded his main denfender. The next time, Worthy shook Purvis Short, waited for Smith to leap, then jumped and spun around him.

“I didn’t know it was going to be a turn,” Worthy said. “That playground instinct just came out. I never practiced that before.” And he has not been able to duplicate the move since.

Jordan, who has missed most of this season with a broken foot, appears to change direction in midair effortlessly, but he says it’s easier to play earthbound.

“On the ground, you control your steps,” he said. “In the air, you can’t. You can’t go around a person.”

But Jordan does, doesn’t he? “It looks like it,” he said. “A lot of times when you change direction, it’s because you got bumped.”

Worthy never rehearses his moves, but Erving takes a studious approach that defies the concept of the “natural athlete.” He sometimes will sit at courtside and think about different ways to expand the court’s dimensions.

For a memorable basket in the 1980 playoff finals, Erving drove down the right side of the foul lane, floated under the backboard with the ball extended out of bounds, then curled under the left corner of the backboard for a reverse layup over Kareem Abdul-Jabbar.

“They don’t know what to do when I’m holding the ball out of bounds,” Ervin said at the time. “Do they go for it? Do they wait for me to bring it back? It has a tendency to freeze defenders. That’s from studying the game – that’s not natural, either.”

Even Erving’s subconscious reaches skyward. He has dreams in which he is flying, which inspires his on-court imagination.

Skywalker By Necessity, Not Nature

As a younger growing up in Roosevelt, Long Island, he most admired Jumpin’ Johnny Green, the 6-foot-5 Knicks forward who often would grab a teammate’s off-target shot in midair and guide it into the basket.

“I always got a kick out of that part of his game,” Erving said.

Erving’s flights of fancy began for more practical reasons. He wasn’t a good outside shooter, so be needed a way to get closer to the basket.

“I started saying, ‘This is wonderful. I can create as avenue for myself and get to the basket, (where) I can jump up and just drop it in.’ It was almost a no-brainer.

“And out on the break, there was the challenge of taking the little guys for a ride.”

Erving’s flights can get dangerously bumpy.

“There’s an electricity that goes through you if you think you should be on the ground and suddenly you’re not,” Erving said. “Suddenly you’re riding on somebody’s shoulder or you get turned around. It’s like a shocking experience and it’s very, very scary.”

After one of those flights, Erving likes to stay on the runway for a while.

How do defenders stop skywalkers? Denver small forward Alex English has the unenviable task of guarding many of them. He doesn’t let his ego get in the way of reality.

“It’s difficult in that they may go over your head, but you use your fundamentals like blocking out and staying on the floor when they shoot,” English said. “Some plays you just have to accept that you can’t do anything.”

Of all the players who specialize in playing in the air, English is most awed by the former NBA star who officially carried the nickname “Skywalker.”

“When I played with David Thompson,” English said, “he did things that just blew my mind.”

Spud Webb Takes Off to New Heights

Photo by Associated Press

By Ron Thomas

Chronicle Correspondent

Dallas

Spud Webb, whose nickname came from a satellite, has reached a new orbit.

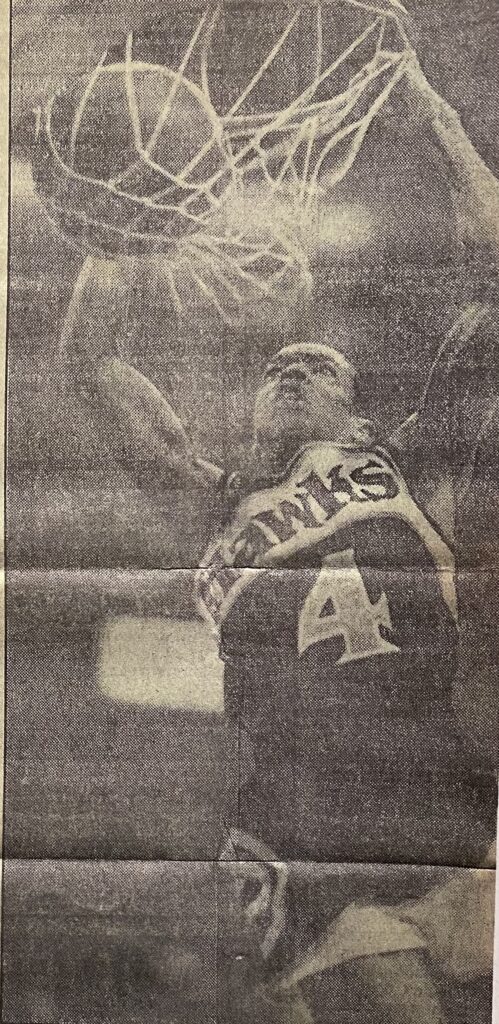

Webb, a 5-foot-7, 133-pound rookie reserve guard for the Atlanta Hawks, is the NBA’s Slam Dunk king, taking the crown Saturday from his best friend among his teammates, 6-7 defending champion Dominique Wilkins.

Wilkins knew Webb could dunk far better than his height would allow, but he didn’t know Webb could defy gravity to make 360-degree spins in the air and still have enough loft left to jam the ball through.

Webb knew that all along, but he can’t explain why he can hang and twirl and spin and jam – even though his hands are so small that he can’t palm a basketball.

“When I figure that out, I’ll write a book about it,” Webb said.

Maybe it’s all in the nickname, Spud. “Everybody thinks it came from a potato, but it came from a satellite,” Webb said.

On his first dunk, he was 5-foot-4

When Webb was a baby, he reminded a friend of his mother’s of a Soviet space satellite called “Sputnik.” Other children shortened it to “Spud,” and now, every basketball fan in America is bound to recognize that nickname, too.

Couple the fact that a 5-7 player won the dunking championship with 6-foot-9 Larry Bird winning the Long-Distance Shootout, and there couldn’t be a better advertising tool for a sport that prides itself on having the world’s best and most versatile athletes.

“Isn’t it great for the NBA?” Atlanta coach Mike Fratello said. “It’s just another thing that will enhance the NBA in the public’s eye.”

Fratello, who also is 5-7, said he can’t imagine anybody who can’t identify with Webb. “When you’re on the bus tomorrow riding to work or on the subway somewhere, you’re saying to yourself, ‘He’s smaller than I am’ or ‘He’s as small as my son is.’

“He’s America. Everybody’s going to be out there tomorrow in their driveway trying to hit the rim.”

Webb spent a lot of time hitting the rim himself before he dunked for the first time. He said he must have tried 100 times before he finally cleared the rim. He slammed for the first time as a 5-foot-4 high school senior.

Since Webb is a Dallas native, he was the crowd favorite all day. (Webb is tied with three others as the smallest players in NBA history: Monte Towe, Red Klotz and Wat Misaka.)

His biggest fan at the contest (rating enthusiasm, not size) was 5-9 former NBA star Calvin Murphy, who had played earlier in the old-timers game. When the judges gave Webb less than a perfect score of 50 on one dunk, Murphy was so agitated he stalked up the sideline toward the judges’ table, frowned like he had smelled a skunk and waved his white cap in disgust. And when Webb stood nearby, you could see Murphy chattering away.

“He was telling me he had (bet) his house on me, so don’t miss,” Webb said.

“We know that the fans wanted Spud to win,” said judge Roger Staubach, the former Dallas Cowboys star. “But we had to be sure that he deserved it. He was more creative.”

A Self-Made ‘Sputnik’

Such as when he threw the ball toward the basket about 15 feet high, caught it on one bounce in mid-air and reverse dunked without touching earth.

And his first dunk, a running two-hand slam, had some accidental flourish. It went through the net, bounced on top of Webb’s head, then bounded back up through the net again.

It was originally ruled a miss until everyone realized Webb’s head had launched its own basketball “Sputnik.”

Webb had performed all of his dunks before, but he didn’t come into the contest with any set plan of dunks. “I didn’t decide what I was going to do until the referee handed me the ball,” he said.

He hadn’t even practiced his routine. “For the last week, I had a sore ankle,” he explained.

“Yeahhhh. Right,” said a skeptical Wilkins. “You must have done some quick healing.”

Next Sunday: Magic Johnson’s “Stolen” Talents