During the late 1980s and 1990s, women’s college basketball was producing superstars who would dominate the WNBA that began in 1997. Among them were Jennifer Azzi, Cynthia Cooper, Lisa Leslie, Rebecca Lobo, Dawn Staley, Sheryl Swoopes and Teresa Weatherspoon. All of them have been inducted into the Basketball Hall of Fame.

The NBA was partly fed by players like Spencer Haywood, Julius Erving and Moses Malone who went straight from high school to the pros or played only a couple years of college ball, but female basketball stars have been developed almost exclusively through their NCAA experiences. The ultimate root of the women’s college game dates back to 1892, when physical training instructor Senda Berenson organized a game between freshmen and sophomores at Smith College just a few months after the sport was introduced to men. Four years later, the first intercollegiate women’s game was played between Stanford and University of California-Berkeley, often called Cal in the sports world.

That game said much less about basketball today than it did about society’s expectations and limitations placed on women when the sport was invented. Here are the roots of today’s article:

Writing an article about the first women’s college basketball game sent me off on a surprising historical and cultural adventure. With Cal Professor Roberta Park as my guide, old San Francisco newspaper stories as my main sources, and the Stanford Library providing photos, I produced this article that appeared in the San Francisco Chronicle on Jan. 20, 1992, to honor 100 years of women’s basketball.

Cal vs. Stanford in 1896: Women’s Game Is Born

By Ron Thomas

Chronicle Staff Writer

When the Cal and Stanford women’s basketball teams play tonight at Cal, their rivalry will have added significance: On April 4, 1896, the two teams played the first intercollegiate women’s basketball game ever.

They played in a San Francisco armory on Page Street the day before Easter Sunday. It was a close game that was tied at intermission. The halftime score? 1-1. In the second half, reported the next day’s Chronicle, Cal committed a “fatal foul,” and Stanford’s Frances Tucker capitalized on it by throwing the ball into the basket for a 2-1 victory.

This year marks the 100th anniversary of women’s basketball, or “basket ball,” as it was written at the time. According to “At the Rim,” a new pictorial history of women’s basketball, Senda Berenson, director of physical training at Smith College, introduced the game to women in 1892, just three months after Dr. James Naismith created the game in Springfield, Mass., which is about 20 miles from Northhampton, Mass., home of Smith College.

The first women’s game was played on March 22, 1893, at Smith, a women’s school where the sophomores beat the freshmen, 5-4. Three years later, Cal and Stanford played the first intercollegiate contest.

That first game didn’t resemble basketball as we know it. There were nine players on a team, and the rules were still evolving.

“It wasn’t very clear to people in the beginning how the game should be played, so people snatched the ball away from each other, and they didn’t know how to throw it into the basket,” said Roberta Park, chairman of Cal’s Department of Physical Education and a specialist in sports history.

And women’s uniforms (called “costumes”) were extremely conservative: heavy woolen garments that covered a player’s entire body except for her face, neck and hands.

No Men Allowed

Naismith, who taught physical education at the International YMCA Training School (now Springfield College), created basketball because his male students needed an indoor winter sport. Park said it was introduced to Cal students by Walter E. Magee, a physical education instructor who had seen it played in Springfield.

At Stanford, one of basketball’s strong boosters was Dr. Clelia Duel Mosher, a staff member in the women’s physical education department who became its director in 1910.

In 1896, the Stanford women challenged Cal to a game in Palo Alto. May Dornin, who wrote a history of early Cal basketball in 1957, quoted the “Berkeleyan” student newspaper saying Cal players refused the challenge. They were “unwilling to have the game played in the open air, or anywhere where a mixed body of spectators can attend,” the Berkeleyan reported.

In other words: No Men Allowed.

Eventually, the teams agreed to the neutral indoor site in San Francisco and the banning of male spectators. Why were the women so concerned about men watching them play?

“Women’s roles, their destiny in life, what they should do and what they were physically and intellectually capable of doing was believed to be entirely different from men – almost diametrically opposed,” Park said.

“Therefore, since the vigorous, powerful and strong was very much part of the masculine role . . . it was strongly believed that not only could women not do this, but if they did it they were violating the rules of nature.”

Also, basketball demanded more exertion than graceful sports like tennis and golf. “If it gets too vigorous, you might get yourself in what were called ungainly poses – you might fall down – and all of these things were just not part of the decorum of the way a young lady should behave,” Park said. “And then you perspired, and women never sweated. Horses sweated, men perspired and women glowed.”

The Chronicle reported that on game day the armory windows were guarded by women holding sticks to keep men from sneaking in. It appears that Mr. Magee was allowed to watch the game because he was quoted in the article, and perhaps Dr. Thomas Wood, Stanford’s director of women’s physical education, was allowed to watch, too.

Emphasis on uniforms

In the Chronicle article, written by Mabel Craft, Magee’s wife, Genevra, (referred to as Mrs. W.A. Magee) and Miss Ada Edwards of Stanford are identified as referees, Miss Moser (presumably a misspelling of Clelia Mosher’s last name) as scorekeeper and a Miss Farnham as timekeeper.

The lengthy Chronicle article (it took half the page, including illustrations) used the very formal writing style of that era. Unlike today’s game stories, which focus on the action, the first third of the article talked almost exclusively about the players’ fashionable uniforms and excellent deportment, which Park said was necessary to prove the game was a respectable activity for women.

“The Berkeley girls have gorgeous hair,” Craft wrote. “Each girl was like a modern Lorelei as she threw back her long mane and braided it in long strands, tied with blue ribbons at the ends and caught up in the way its owner deemed securest.

“. . . the Stanford girls made quite as pretty a picture. Their sweaters were cardinal and masculine in cut, worn over the bloomers without belts and trimmed with wide red sailor collars. Their bloomers were an assorted lot. Some were brown, some blue, some black . . . all wore bewitching polo capes of bright red, with tassels.”

Craft characterized the players as “two different California types.” Stanford players were “small, slender, sinewy. Some were rounded, but most of them were agile, without an ounce of superfluous flesh.” The Cal players were “bigger, stronger, heavier, slower . . . They were more sedate and less vivacious, but not less eager and scarcely less alive than the Palo Alto girls.”

Basketball, 1896 Style

The rules of the game sound strange to us now. “The ball is caught and instantly thrown,” Craft wrote. “No one is allowed to fall on it and stay there. Five feet is the furthest you can run with it, and five seconds the longest you can hold it, and all in all, it’s the jolliest kind of a romp.”

Then she noted that the game was invented for men – “there isn’t anything effeminate about it” – and that physicians who believe women are “so delicate” would become hysterical watching them play it.

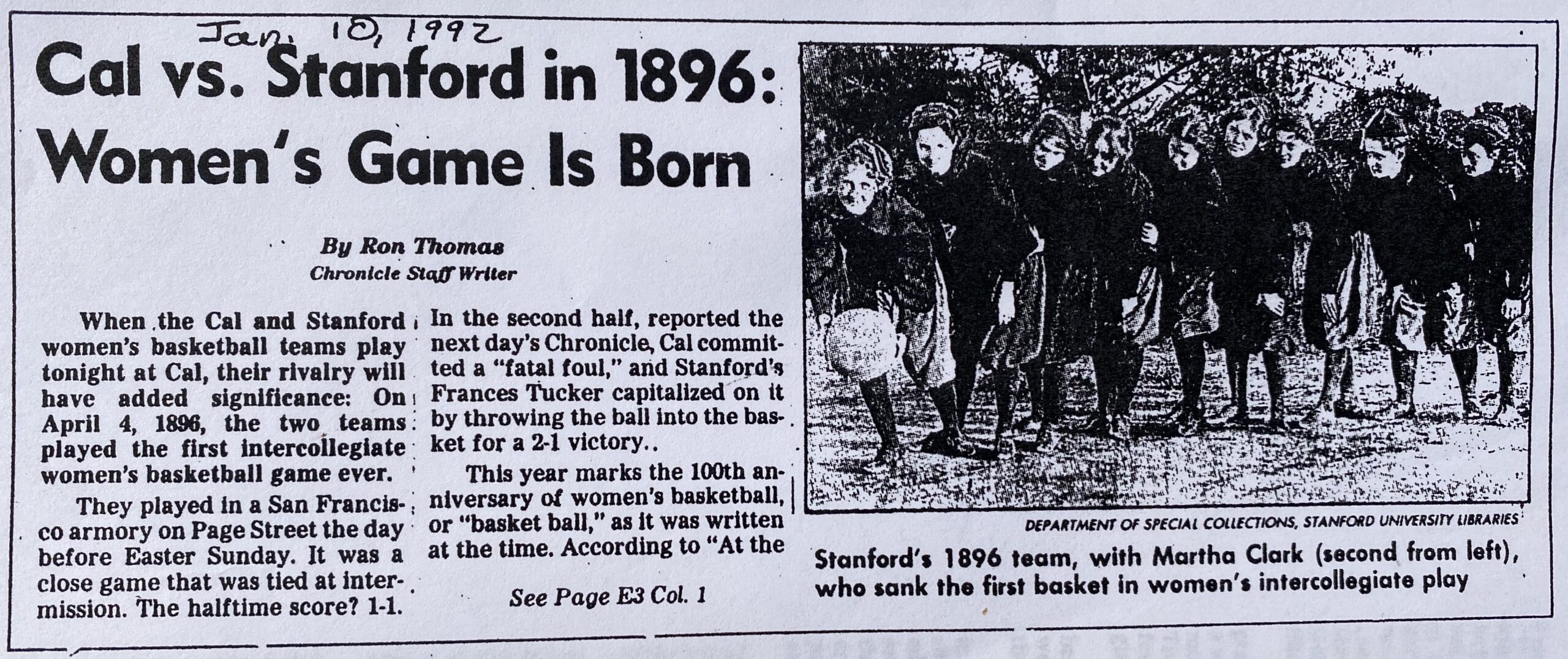

Stanford’s Martha Clark sank the first basketball in women’s intercollegiate history, which at the time counted for only one point. “It came after a most exciting rush, when the ball, like a cork, had been from end to end of the hall for 10 minutes,” Craft wrote.

The ball stuck in the basket, which was made of netting, so someone jerked a string attached to the basket and “it belched out its contents,” then the game resumed. About five minutes later, Katherine Jones scored for Cal, tying the game, 1-1.

Then a crisis arose. Stanford’s basket was lopsided, so the janitor and a helper, both men, were allowed in to straighten it. Dornin, citing a San Francisco Examiner article, said the Cal women “modestly retreated” into a huddle at the far end of the court, but the Stanford players “boldly” sat down in the middle of the floor.

At halftime, both teams rested in their dressing rooms and sucked on oranges for nourishment. Craft reported that, “One tearful mother was at the door. ‘I was afraid you were killed, dear,’ she said, ‘when you got that terrible fall, with that great big girl on top of you.”

“Not a bit of it,” her daughter replied. “I’m all right. Go back and don’t bother.”

When Cal fouled Frances Tucker during the second half, Tucker’s ensuing shot scored the winning point.

“The scene that followed was wild,” wrote Craft. “Somebody had an arm around the neck of every red sweater, the little red caps flew in the air and fluttered down anywhere.”

In the next few years, Cal continued to play games against local colleges, high schools and YMCAs, and Stanford women played weekly games against each other. In 1899, a Stanford faculty committee banned women from playing intercollegiate contests in all sports, and Cal’s women were discouraged from intercollegiate action because they couldn’t practice in Harmon Gym, which was being remodeled.

But they defied those orders and played again on April 23, 1900, a 7-0 Stanford victory. Tonight’s game at Harmon Gym is a tribute to their determination and their love for the game of basketball.

Next Sunday: How Bird Took Off